Recently, I’ve been entranced with a book called Tony Duquette, which is a 2-inch-thick coffee table photo-biography about the design life of the iconic Hollywood interior, costume and set designer by the same name.

Recently, I’ve been entranced with a book called Tony Duquette, which is a 2-inch-thick coffee table photo-biography about the design life of the iconic Hollywood interior, costume and set designer by the same name.

Known for his innovative use of materials that others may not value (cast-offs from old movie sets, flea market finds, repurposed and salvaged goods), Tony Duquette embraced the potential and possibility in everything around him. He seemed to see the higher and better use of even the most prosaic object. Case in point was the description of a garage he and his wife Beedle Duquette, a painter, appropriated for entertaining. According to the book’s authors Wendy Goodman and Hutton Wilkinson,

” . . . Tony believed garages to be a useless waste of space and always converted his into sitting rooms.” He was quoted as saying: “When the party is over, just roll up the rug and drive the car in. It’s really the only thing to do in a house as small as this one.”

I’ve long admired this level of practicality combined with architectural artistry. While paging through Alex Johnson’s awesome new book Shedworking, I realized that Duquette’s inventiveness has a modern-day companion – the self-employed individual setting up shop in a garage-as-workspace. It’s an idea as compelling as the 1960s hipster and his garage-turned-party room.

Here's Alex's home-office where it all started

Alex Johnson, a Shedworking evangelist

In Shedworking: The Alternative Workplace Revolution (Frances Lincoln, 160 pages; 150 color photos, $29.95), Alex finds and documents an entire community of people for whom the useful shed is a way of life.

Ever since we first “met” online in 2006, while I was writing and creating my U.S. take on this trend in Stylish Sheds and Elegant Hideaways, I’ve been waiting for this book’s arrival – to add to my Shed Inspiration bookshelf.

Like his popular blog, also called “Shedworking,” Alex’s Shedworking is a compilation of the many ways that people can make a living in a nontraditional environment. Alex coined the term “Shedworking” in 2005 and he has been reporting on this not-so-quiet revolution ever since, including with the publication of an online magazine called “The Shed” that addresses the needs of at-home workers.

I love, of course, the structures called “Garden Offices,” which seem to so naturally occupy arboretum-like or city-vegetable patch environments. There are also some amazing cutting-edge architectural examples and mini-profiles of famous “shed owners,” such as Henry Moore. History gets into the pages of Shedworking, with a visit to Walden Pond and a replica of the famous cabin (okay, let’s call it a “shed”) from which Henry David Thoreau issued his own manifesto about living, creating and cohabiting with nature.

“Over the last decade we have seen an evolution of the office workplace,” Alex writes in his introduction. “A small shed which once only housed lawnmowers and pots can now be insulated from the cold, fitted with its own electrics, and can link you to anywhere in the world.”

You can tell that Alex and I are kindred spirits, since I endorse much the same approach to reimagining the garden shed in my own book. While I focus on the design, repurposing and artfulness of the structures (inside and out), Alex puts a big emphasis on the functionality of the sheds he profiles. Yet the designs in his “Best Sheds” chapter totally wow me. There are some cool American-made pre-fabricated structures, including the Kithouse, Modern Cabana and Modern Shed, three structures I reviewed last year for Dwell magazine, and the Nomad Yurt, which I reviewed here when it was first exhibited in Los Angeles in 2008.

But there are countless surprises in style and sustainability. Take a look at TSI (Transportable Space One), a mirrored structure that reflects the garden surroundings, designed by an Australian firm. Or the “Orb,” which is soon to come into production. It is a lightweight oval with four adjustable legs, a modern-day caravan-like structure. Another dazzling “pod” for the contemporary home-worker: The Loftcube, designed by a team in Berlin, is a glass-and-wood combo that can be “helicoptered onto your roof” to create a skyscraping rooftop office.

-

-

The Loftcube, by Werner Aisslinger of Studio Aisslinger, Berlin

-

-

The Orb, from Philip Simpson and David Miller of the UK.

-

-

TS1: Transportable Space One, from Nadja Mott of Pluscreate in Australia

The contents of Alex’s “Best Sheds” chapter are pretty breathtaking. You can come down to earth a little bit by reading his “Build Your Own” chapter. This section is for DIYs (do-it-yourselfers) or those who have an idea and hire a specialist to help execute it. Alex’s sidebar: “How I set up my own garden office,” is engaging and personal – fun way to get to know this talented writer and fellow shed aficionado. “9 Essential Questions to Ask Yourself before You Start Building Your Own Shed” is another very useful checklist. It was written by John Coupe, civil engineer and owner of www.secrets-of-shed-building.com.

Naomi and James once lived in this structure for six months while constructing their new home.

I’m also pleased to see that Alex published and profiled Naomi Sachs’s office shed in Beacon, New York. Naomi, an expert in therapeutic landscape design, and I corresponded back in 2007 when I was working on my Shed book – and I’m still disappointed that I never got to visit her studio/shed while my collaborator Bill Wright and I were working on the East Coast. It’s nice to see the soulful structure Naomi and her partner James Westwater created show up here. (I’ve added Naomi to my ever-growing list entitled: “The ones that got away” – cool shed environments we wish could have been included in Stylish Sheds). Oh well!

A subsequent chapter covers “At Work in the Shed,” with snapshots of the vocational uses for a shed (including a filmmaker, designer, architect, journalist, web developer, painter, letterpress artist, academic, massage therapist, writer, cheese maker, sculptor, jewelry maker, management consultant and novelist).

“But does shedworking actually work?” Alex asks his readers. “Is it more than an attractive ideal? Can you run a successful business from your back garden? The pleasing answer is yes. . . . many people who are alternative workplace revolutionaries not only enjoy the micro commute to work and the chance to fill up the bird feeder on the way, they also make money.”

“The Green Shedworker” features sustainable building and design ideas, green roofs, tree house sheds, and a sidebar on “Five ways to incorporate your garden office into your garden.” Naturally, I agree with the wonderful tips shared here, including this one: “aim for the studio style to be in keeping with the garden, so for example a modern studio for a modern garden.”

Alex turns his attention to future shed trends as he wraps up Shedworking. These chapters reveal his progressive outlook on the changing work environment. A true visionary, Alex thinks big; he sees the potential where others see the hard-to-achieve. He pushes the envelope when it comes to workplace design and is a shed missionary in the most inspiring sense of the word.

“Beyond the Garden Office” is a chapter that looks at futuristic ideas for the workplace, the virtual office and the mobile lifestyle. From retro Air Stream trailers to working environments on canals, by the seaside or in a London Tube train, Alex’s examples dissolve assumptions and say to the reader:

“The truth is that neither size nor location matter when it comes to setting up as a shedworker. . . the future is shedshaped, psychologically, even if not physically.”

A final chapter is even more forward thinking, as it explores the landscape normally occupied by policymakers. The small structure (aka Shed) used for emergency housing, low-carbon-footprint environments and other residential off-grid experiments are ones that fascinates Alex Johnston.

His benediction of sorts is to urge those trapped in an office cubicle to view the Shed-Office as Nirvana:

“. . . for many office workers who can’t remember the last time they had lunch away from their desk or who never see natural light during the day, (the shed) is a beacon of hope.”

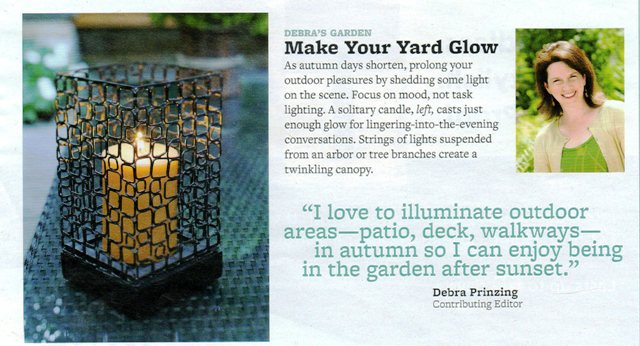

October is well underway, and here is my little “Know-How” piece from the October 2010 issue of Better Homes & Gardens.

October is well underway, and here is my little “Know-How” piece from the October 2010 issue of Better Homes & Gardens.

Here are some additional “illuminating” ideas for your after-dark garden enjoyment:

Here are some additional “illuminating” ideas for your after-dark garden enjoyment:

The flowers that Marie Lincoln and Bill Schlicht cultivate at their Whidbey Island nursery specialty nursery are good enough to eat. That’s because

The flowers that Marie Lincoln and Bill Schlicht cultivate at their Whidbey Island nursery specialty nursery are good enough to eat. That’s because