by Maxwell Tielman

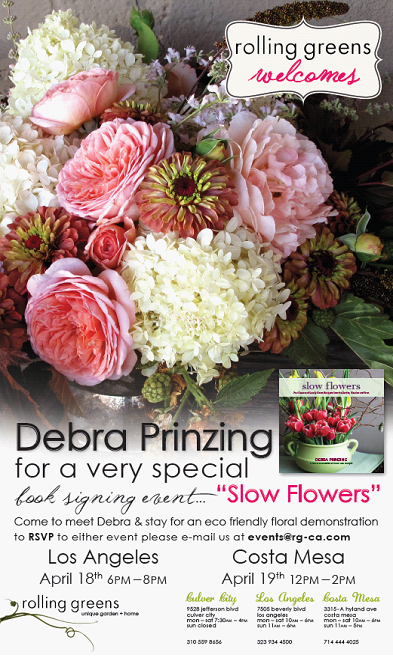

INTERVIEW: DEBRA PRINZING OF 50 MILE BOUQUET & SLOW FLOWERS

Here is a link to the DESIGN*SPONGE page

Over the past year or so, I have been trying, to the best of my ability, to live “slow.” While living slowly doesn’t necessarily mean halting one’s motions or moving at a snail’s pace, it does mean taking time away from the deleterious modern-day practice of Me-Want-It-Now. Whether I’m enjoying slow art, enjoying the pleasures of slow food, unwinding with a knitting project, or just learning to give myself some time to think, I’ve found that the concept of “slow” has amazing benefits, for the self and for the environment. While slow food and all it entails (eating locally, seasonally, organically, etc.) is often at the forefront of the slow/sustainable discussion, the concept really expands far beyond what we put on our plates. The act of choosing local vs. imported or organic vs. conventional has similar consequences whether you’re talking about food, furniture, or even flowers. Indeed, although flowers are often an afterthought to most consumers, picked up at the supermarket or bodega for a quick pick-me-up, the same rules apply when it comes to these tiny living things. Despite the fact that flowers may seem like a superfluous “luxury,” where they are sourced, how they grown, and who they are purchased from do make a difference, both in terms of your health and the environment. Debra Prinzing, a West Coast author and Outdoor Living Expert, has devoted much of her working life to educating people about the benefits and pleasures of raising and purchasing sustainably grown local flowers. In last year’s The 50 Mile Bouquet, Prinzing took readers on a nationwide tour of sustainable flower farms and shops, providing a few tips and ideas along the way. This year, she unveiled her latest effort, Slow Flowers, a compendium of locally-sourced seasonal bouquets, one for each week of the year. Debra took some time to chat with us about slow flowers and some of the challenges and joys that come with the act of thinking about flowers in a more sustainable way. Check out the full interview after the jump! —Max

Here I am in my favorite flower field, surrounded by dahlias (c) Mary Grace Long photograph

Debra: Many people consider flowers a “luxury” or an indulgence (although I disagree – I believe bringing flowers into our homes is an essential, life-affirming way to connect with nature!). But if you take the position that flowers are a luxury, then I would argue it’s all the more reason to be responsible in the way we consume them. Buying imported flowers that have been produced with low-cost labor, in countries that do not have as stringent environmental standards as the U.S., which are THEN shipped to us on chartered cargo planes using tons of gallons of jet fuel – how is that sustainable?

Locally-grown flowers may cost a few dollars more per bunch, but when you buy them, you are supporting a family-owned farm (and farm jobs), preserving farm land, encouraging rural economic development and reducing carbon dependency.

Design*Sponge: The American consumer has grown so accustomed to a year-round availability of not just food, but flowers, that it might be difficult to convince him or her to revert to a more “seasonal” lifestyle. What are the benefits, both personally and environmentally, of making the move to seasonal and local flowers?

Take a visual “whiff” and enjoy this combination of three lovely flowers.

Debra: If you are a foodie, and if you embrace a seasonal, farm-to-table approach in your menu or dining choices, then you probably understand the term “slow flowers.” To me, the beauty of this practice is being observant of the seasons and appreciating each flower as a moment in time.

Sure, this might mean a less abundant selection of winter-season flower choices, but we also have a less abundant winter selection of local food. Think about a January tomato, one that you bring home shrink-wrapped from the supermarket: it’s mealy and basically tasteless. Wouldn’t you rather enjoy a heirloom tomato, picked right off the vine, in July or August? That’s flavor as it is meant to be tasted.

Similarly, out-of-season flowers can seem lifeless, scentless and, well, out of season! I like to say to brides: If you want to walk down the aisle carrying peonies, then get married when peonies are in bloom (note: this means May or June). I realize that floral artists (and wedding parties) do not want limited choice, but increasingly, there are brides asking for all local flowers (just like an all-local catering menu) and this, inherently, means those flowers will be in season.

Gardeners, of all people, really understand this notion. If you’re in tune with your personal backyard (patio, deck or windowsill), you know what blooms when — that’s what seasonality is all about. For me, that means my Seattle garden provides conifer branches and colorful twigs during the winter months. I’m happy to wait until spring arrives for my bulbs to bloom and I celebrate the advent of luscious dahlias in August. I definitely anticipate each season with each new bloom cycle.

By the way, I’m not super-rigid about seasonality. Thanks to the season-extension efforts of many American flower farmers, you can find early- or late-blooming floral options grown in hoop-houses or greenhouses — providing enough extra floral bling to satisfy one’s cravings weeks before spring really arrives or months into December. I’m lucky here in the Seattle area, because we have Alm Hill Gardens, a farm near the Washington-B.C. border, that grows organic tulips and sells them almost year-round at the Pike Place Market. One of my favorite rituals is to head down to the market and select tulips from Gretchen or Ben or Max – the farmers I’ve grown to appreciate for the healthy, vibrant crops they produce.

Design*Sponge: What do you think are some of the biggest misconceptions held by consumers about local or sustainable flowers?

Design*Sponge: What do you think are some of the biggest misconceptions held by consumers about local or sustainable flowers?

Debra: The biggest misconception is understanding where flowers come from. A majority of consumers don’t know. Flowers just mysteriously appear in buckets at the supermarket and many people never consider their origin.

When the California Cut Flower Commission conducted a national survey a few years ago, they asked: “Do you know where your flowers come from?” and a shocking 85% answered “No.” [Interestingly, in answer to the follow-up question — “If given a choice, would you buy California-grown flowers? — 55 percent of respondents said “Yes.”]

People need correct information about the flowers they buy. Because there is no required country-of-origin labeling (such as with produce), there has not been a good way for consumers to determine the source of their flowers. Sadly, because of this, we have low expectations from the flowers we purchase, especially those stocked at supermarkets or by mass merchants outlets. We expect our flowers to be cheap because we don’t expect them to last long in a vase. Many are probably imported — a far cry from fresh and local.

The only way to change this is for flower consumers to always ask: Where were these flowers grown? and How were they grown?

I interviewed Max Gill, a SF floral designer who creates the bouquets for the famed Berkeley farm-to-table restaurant Chez Panisse. He told me he shops at the SF Flower Market and says to the vendors: “What did you grow that you did not have to spray?” Max went on to explain: “. . . by making it really clear where my dollar will go, I feel strongly that I’m including everybody in the ‘sustainable’ conversation.”

Gretel and Steve Adams, my flower farmer pals from Ohio, owners of Sunny Meadow Flower Farms.

Design*Sponge: Many flower enthusiasts might be interested in purchasing more sustainable, environmentally friendly flowers, but are unsure of where to begin or look. What are some questions one should ask when looking for sustainable flowers?

Debra: Know your flower farmer. Start with local growers – the best place to meet them is at your community farmers’ market. Talk with them and learn about their growing practices – they love to share their knowledge.

You do have to be a bit of a sleuth. One way to find growers in your own state is to search the free database of the Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers (www.ascfg.org – click on the Growers tab and search by state). Many of the members of ASCFG will sell direct to the consumer; some have seasonal U-pick farms; others will tell you which markets or florists carry their seasonal blooms. Look for “local labeling.” Flower farmers in many states voluntarily label their bouquets. I’ve seen logos for Alaska, California, Colorado, Illinois, Texas and Wisconsin-grown, to name a few.

I have to add a clarification here about the word “sustainable,” which has so many meanings and is a vague term. It’s very difficult for a small flower producer to gain USDA organic labeling (the regulations are clearly set up for food production; not flower production – and it is costly). But even if they don’t use the phrase “sustainable,” I can tell you that ALL AMERICAN-GROWN flowers are more sustainable than any imported ones. We have stricter environmental regulations in the US than in any flower-exporting country. In addition, the carbon footprint alone required to import flowers makes them less sustainable than domestically grown flowers. Locally grown is always going to be more “green” than imported.

And some regions have their own ways of alerting consumers that products (including flowers) are sustainable. In the Pacific Northwest, flower farmers participate in Salmon Safe (http://www.salmonsafe.org/flowers), which is a third-party environmental organization that designates whether farm practices are safe for salmon habitat.

Design*Sponge: Depending on the source you get your flowers from, they may or may not be labeled as sustainable or local. Additionally, depending on your locale, there might not be a sustainable florist or farmer’s market within reach. Are there any varieties that are more commonly grown locally, or at least domestically?

Debra: Annual and perennial flowers, such as sweet peas, cosmos, sunflowers, zinnias, calendulas, nigella, bread seed poppies, Queen Anne’s lace, phlox, yarrow and so many others are likely to be locally-grown. These simply don’t ship well and therefore are probably not imported. Spring-flowering bulbs and flowering branches are also likely to be local or domestic. Garden roses, old-fashioned flowering shrubs (lilacs, viburnum, some hydrangeas); summer bulbs like dahlias — these are best when supplied from local farms.

Oregon-grown roses from Peterkort – healthy, sustainably grown and simply beautiful!

Design*Sponge: On the flip side, are there any varieties an earth-conscious consumer should avoid at standard flower stands?

Debra: Do you mean “conventional florists?” The wire-services are the biggest culprits in marketing and selling mass-produced, imported flowers to consumers. Most roses are imported. It makes me sad that even our so-called “green” grocery stores promote imported roses as sustainable, which to me feels like green-washing. I call South American-grown roses “softball-on-a-stick.” Big heads; fat, rigid stems; NO fragrance. That look and shape are giveaways for roses that have been bred for “ship-ability,” if that’s a word.

Domestic roses, which are still grown by family farms in Oregon and Washington, are hybrid teas or spray roses. These are more feminine and delicate (with slender stems) smaller heads and light to intense fragrance, depending on the variety. Here are a few sources for American-grown roses:

Wholesale, but you can ask your florist to order for you:

Peterkort Roses from Oregon

California Pajarosa

Direct to consumers:

Eufloria Flowers from California

David Austin cut roses from California

Rose Story Farm cut roses from California

Here are the American made vases (and their marks) I love to use.

As a design website, our readers are often looking for ways to incorporate beautiful objects into their lives. Although your work focuses primarily on sustainable horticulture, the concept of sustainability certainly extends beyond living things to design objects. Do you have any go-to sources for beautiful, locally-made flower containers and gardening tools?

Debra: never thought I would be such a proponent of American Grown/American Made, but after writing The 50 Mile Bouquet and Slow Flowers, I appreciate the value and importance of promoting both domestic farms and domestic manufacturers. Even my books are printed in North American (not Asia!), on FSC certified paper with soy-based inks. I have my publisher to thank for making the choice to not print overseas.

Here are some of my favorite USA-Made floral resources:

Florian floral snips (for herbaceous and woody stems)

Thorn strippers (for stripping rose stems), designed by a floral designer and made in the USA

Vase Brace: A tray with bungee-style cords on all four corners, which makes it easy to transport a vase filled with flowers by car

Raw Materials work aprons

Bauer California pottery (wonderful vases, made in California)

Vintage American vases are easy to find online or at flea markets. Look for makes such as Floraline, McCoy, Haegar, Royal Copley, (vintage) Bauer and more.

**Sadly, I am still looking for USA-made women’s gardening gloves. No luck yet!

Summer dahlias remind me of my Grandad Ford’s wonderful dahlia garden.

Spring peonies remind me of my Grandpa Prinzing’s peony beds.

Design*Sponge: Your book covered a wide range of flower types and growers. What are your personal favorites— both in terms of flowers and your own local flower sellers?

Debra: Oh, what a question! I think childhood flower memories are incredibly powerful, and my personal family memories have formed my flower preferences. My maternal grandfather grew dahlias in his Indiana backyard; my paternal grandfather grew peonies in his Illinois backyard. Flower-growing skipped my parents’ generation and yet those genes came to me. I cherish dahlias and peonies to this day, thanks to my grandfathers’ flower beds.

Living in Seattle, I have the privilege of calling so many flower farmers my personal friends. They have welcomed me onto their farms and generously shared their growing secrets. Earlier this year, I joined the board of Seattle Wholesale Growers Market, our Northwest farmer-to-florist cooperative of about 15 Oregon, Washington and Alaska farms. The SWGMC is open to the public on Fridays, 10 a.m.-2 p.m., so anyone can shop for flowers direct from the farmer.

It has been a great experience to work with this group, rubbing shoulders with experienced growers and learning about their passion for heirloom varieties, unique floral crops and sustainable practices. This week at the market offers a snapshot of the incredible diversity of the moment; hellebores, snowdrops, grape hyacinths, euphorbia, pussy willow, calla lilies, tulips, daffodils, anemones, poppies, flowering dogwood, bridal wreath spirea, snowball viburnum – and some ingredients I’ve probably forgotten. It is mind-blowing and a floral designer’s dream.

Design*Sponge: What can others do to spread the word about sustainable flower production? What actions can be taken to introduce sustainable flowers to your region?

Debra: The first thing you can do is grow your own flowers! Even if you just start by sowing one packet of sweet pea seeds, you will bring local flowers into your life. You can even grow a few in a pot with a trellis to train the vines — a small space cutting garden!

Next, seek out flower farmers in your area. If readers are stumped, they can email me and I’m happy to connect them with a grower in their region. There are passionate flower farmers in every state. Buy American Grown whenever possible and ask your local suppliers to verify the source of the flowers they stock.

Follow #Americangrown, #flowerfarmer, #originmatters and #slowflowers on Twitter to find more activity in the domestic flower world.

If you are interested in learning more about becoming a flower farmer, visit www.ascfg.org